澳门最精准免费资料大全旅游团,2025澳门六开彩免费精准大全,2025澳门特马今晚开什么,2025澳门天天彩期期精准,2025澳门天天开好彩大全2025,2025澳门天天开好彩大全46期,2025澳门天天开好彩大全53期,2025澳门天天开好彩大全免费,2025澳门天天开好彩大全香港,2025澳门天天开好彩精准24码,2025澳门天天开好彩资料?,2025澳门天天六开彩开奖结果,2025澳门天天六开彩免费图,2025年澳门精准免费大全,2025年澳门天天开好彩,2025年天天开好彩资料,2025年新奥正版资料免费大全,2025年新澳门天天彩开彩结果,2025年新澳门天天开彩,2025全年资料免费大全,2025新奥精准正版资料,2025新奥正版资料免费,2025新澳精准资料大全,2025新澳精准资料免费,2025新澳精准资料免费提供下载,2025新澳门今晚开特马直播,2025新澳门天天开好彩大全孔的五伏,2025新澳门天天开好彩大全正版,2025新澳门天天六开彩,2025新澳正版免费资料大全,2025新澳资料大全免费,2025新澳资料免费大全,2025正版资料免费公开,澳彩资料免费的资料大全wwe,澳门内部最精准免费资料,澳门天天六开彩正版澳门,澳门正版资料大全资料贫无担石,澳门最准的资料免费公开,新奥天天免费资料大全正版优势,新奥资料免费精准期期准,新澳2025今晚开奖资料,新澳2025资料大全免费,新澳精选资料免费提供,新澳精准资料免费提供,新澳门今晚开特马开奖,新澳天天彩免费资料2025老,新澳天天开奖资料大全最新54期,新澳天天开奖资料大全最新54期129期,新澳资料免费精准期期准,新澳最精准免费资料大全

港彩高手出版精料

澳门精华区

香港精华区

- 197期:【贴身侍从】必中双波 已公开

- 197期:【过路友人】一码中特 已公开

- 197期:【熬出头儿】绝杀两肖 已公开

- 197期:【匆匆一见】稳杀5码 已公开

- 197期:【风尘满身】绝杀①尾 已公开

- 197期:【秋冬冗长】禁二合数 已公开

- 197期:【三分酒意】绝杀一头 已公开

- 197期:【最爱自己】必出24码 已公开

- 197期:【猫三狗四】绝杀一段 已公开

- 197期:【白衫学长】绝杀一肖 已公开

- 197期:【满目河山】双波中 已公开

- 197期:【寥若星辰】特码3行 已公开

- 197期:【凡间来客】七尾中特 已公开

- 197期:【川岛出逃】双波中特 已公开

- 266期:【一吻成瘾】实力五肖 已公开

- 197期:【初心依旧】绝杀四肖 已公开

- 197期:【真知灼见】7肖中特 已公开

- 197期:【四虎归山】特码单双 已公开

- 197期:【夜晚归客】八肖选 已公开

- 197期:【夏日奇遇】稳杀二尾 已公开

- 197期:【感慨人生】平特一肖 已公开

- 197期:【回忆往事】男女中特 已公开

- 197期:【疯狂一夜】单双中特 已公开

- 197期:【道士出山】绝杀二肖 已公开

- 197期:【相逢一笑】六肖中特 已公开

- 197期:【两只老虎】绝杀半波 已公开

- 197期:【无地自容】绝杀三肖 已公开

- 197期:【凉亭相遇】六肖中 已公开

- 197期:【我本闲凉】稳杀12码 已公开

- 197期:【兴趣部落】必中波色 已公开

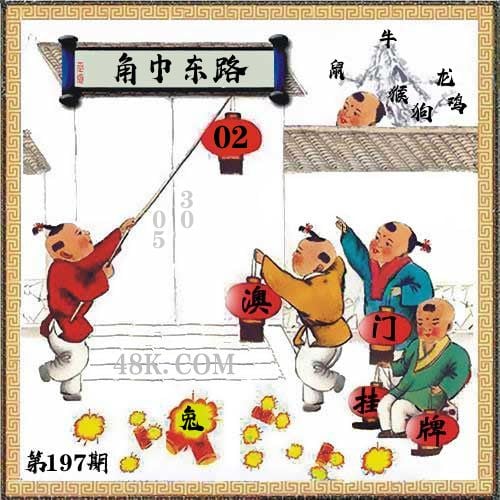

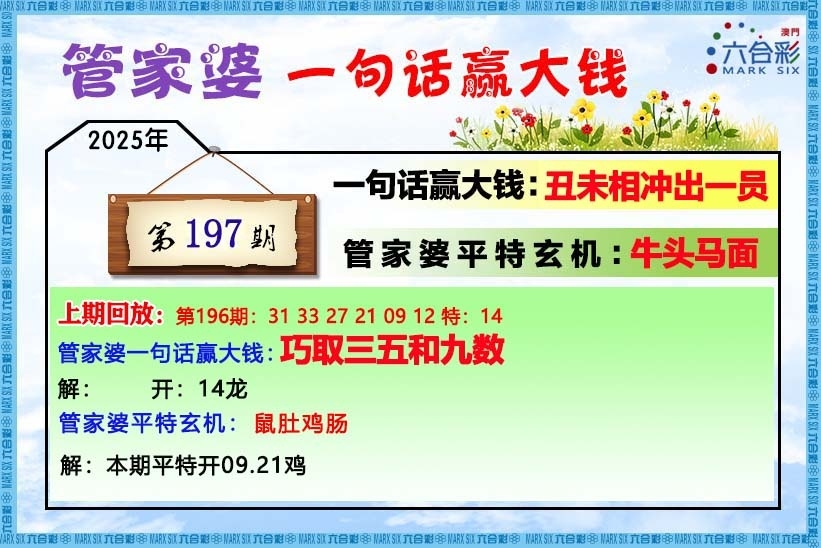

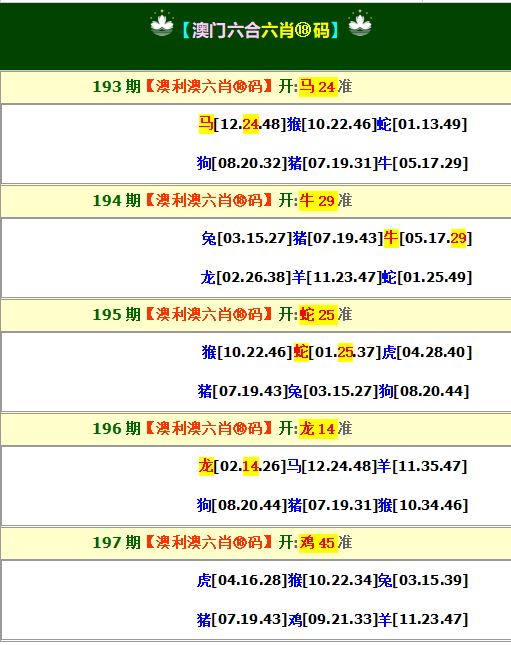

【管家婆一句话】

【六肖十八码】

澳门正版资料免费资料大全

- 杀料专区

- 独家资料

- 独家九肖

- 高手九肖

- 澳门六肖

- 澳门三肖

- 云楚官人

- 富奇秦准

- 竹影梅花

- 西门庆料

- 皇帝猛料

- 旺角传真

- 福星金牌

- 官方独家

- 贵宾准料

- 旺角好料

- 发财精料

- 创富好料

- 水果高手

- 澳门中彩

- 澳门来料

- 王中王料

- 六合财神

- 六合皇料

- 葡京赌侠

- 大刀皇料

- 四柱预测

- 东方心经

- 特码玄机

- 小龙人料

- 水果奶奶

- 澳门高手

- 心水资料

- 宝宝高手

- 18点来料

- 澳门好彩

- 刘伯温料

- 官方供料

- 天下精英

- 金明世家

- 澳门官方

- 彩券公司

- 凤凰马经

- 各坛精料

- 特区天顺

- 博发世家

- 高手杀料

- 蓝月亮料

- 十虎权威

- 彩坛至尊

- 传真內幕

- 任我发料

- 澳门赌圣

- 镇坛之宝

- 精料赌圣

- 彩票心水

- 曾氏集团

- 白姐信息

- 曾女士料

- 满堂红网

- 彩票赢家

- 澳门原创

- 黃大仙料

- 原创猛料

- 各坛高手

- 高手猛料

- 外站精料

- 平肖平码

- 澳门彩票

- 马会绝杀

- 金多宝网

- 鬼谷子网

- 管家婆网

- 曾道原创

- 白姐最准

- 赛马会料

A

B

C

D

E

[(备案号)]

友情链接:百度一下

"*"是广告/外链,所有内容均转载自互联网,内容与本站无关!

谨供娱乐参考!严禁转载、盗链等一切不法行为!

Copyright ©2010 - 2025 - 澳门天天好彩 版权所有